You’ve likely heard the term ‘reverse dieting’ thrown around, and if you’ve spent any amount of time trying to eat less, cut back, or control your intake, the idea of doing the opposite might sound both intriguing and a little confronting. After all, wouldn’t eating more just mean gaining weight?

Before we jump to conclusions, let’s break it down. What actually is reverse dieting, and when (or if) should you consider it?

What is Reverse Dieting?

Reverse dieting is a structured increase in energy intake (calories/kilojoules from food) with the goal of supporting metabolism. You might have heard terms like diet breaks, refeeds, or returning to ‘maintenance’ calories – all of which are variations on the same concept.

We live in a world obsessed with ‘calories in vs. calories out,’ where the message to eat less is everywhere. But what happens when we don’t eat enough for too long?

How Does Reverse Dieting Work?

While the idea of calories in vs. calories out seems simple – eat more, gain weight; eat less, lose weight – the reality is much more complex.

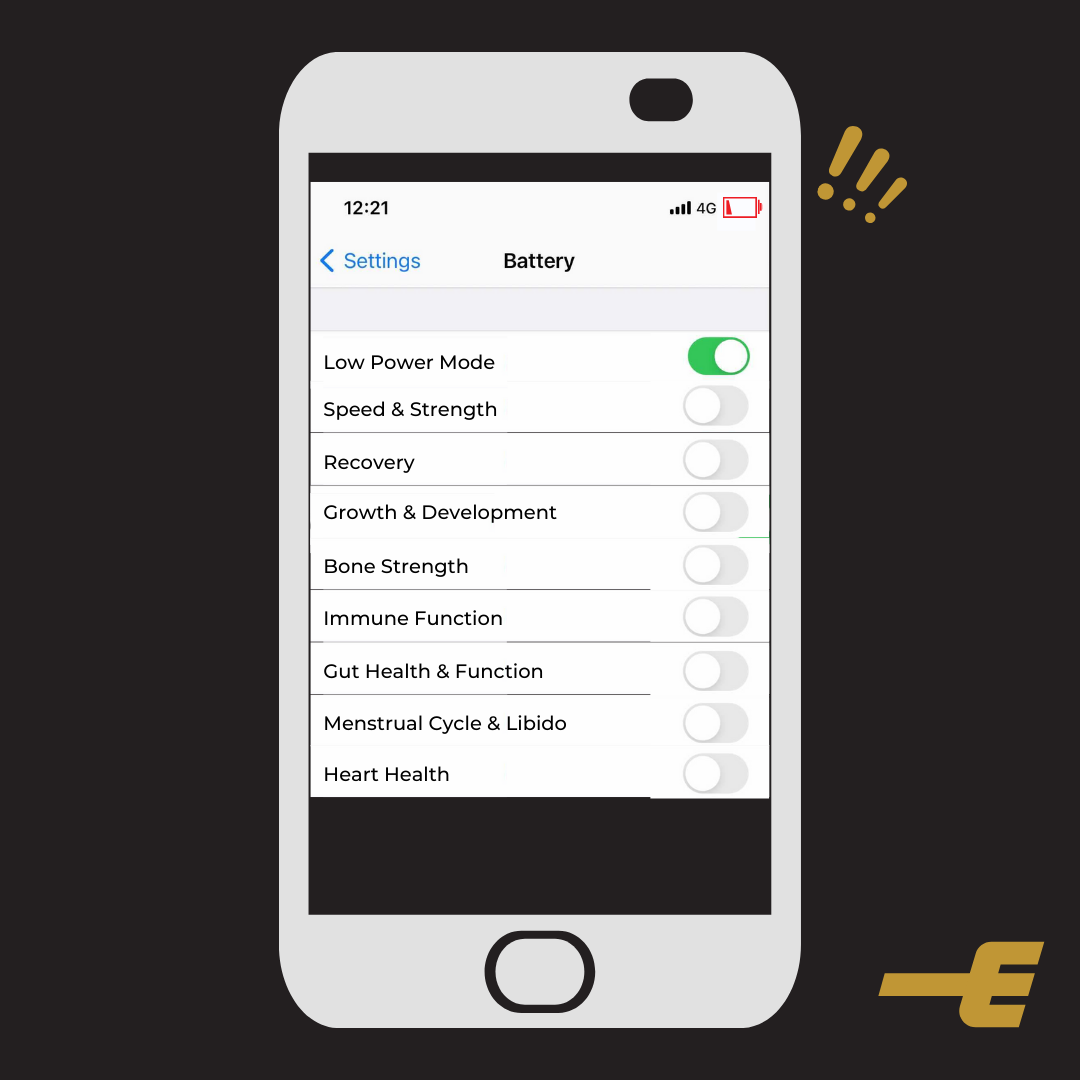

Our metabolism is dynamic and adapts based on how much energy we provide. If we eat less than our body needs to fuel daily functions, training, and recovery, it adjusts by slowing down – a process known as metabolic adaptation. Think of it like putting your phone on low-power mode. Your body becomes more efficient at using less energy, which can lead to fatigue, sluggish recovery, and other disruptions in health.

So, if we gradually increase intake (like plugging your phone back in to charge), can we reverse this adaptation and restore metabolism? And does eating more necessarily mean weight gain?

Why Would You Consider Reverse Dieting?

If you’ve been in a cycle of restrictive eating, aggressive dieting, or simply underfuelling, increasing your intake may help you feel and perform better. The goal isn’t just to ‘reverse’ a diet – it’s about rebuilding energy availability and food confidence.

Signs that you may be in Low Energy Availability (LEA) and experiencing metabolic adaptation include:

- Frequent illness or injury

- Persistent fatigue

- Ongoing gut discomfort

- Eating less than those around you but still struggling with body composition

- Lack of progress in strength or endurance training

- Changes in hormones, including missing periods or low libido

- Low mood, irritability, or trouble concentrating

Eat more, lose weight?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer to this. While some people see body composition changes, the bigger question is: what does success mean for you? If your only definition of success is weight loss, any fluctuation in weight may feel uncomfortable. That’s why working with a professional can help navigate this process in a way that aligns with your values and goals.

What we do know is that eating in a state of energy availability can improve gut health, immune function, hormone balance, training adaptations, and even cognitive function. More energy in often means better sleep, concentration, and mood – things that impact performance in all areas of life.

Beyond Physique – Relationship with Food

If your food choices are driven by fear, anxiety, or rigid rules, the priority isn’t just reverse dieting – it’s healing your relationship with food. Long-term restriction can affect not just metabolism, but mental well-being. Studies on prolonged under-eating have shown significant impacts on mood, brain function, and decision-making.

Adding energy back in can help, but the best approach is one that considers both physical and mental health. That’s where we come in.

What Now?

If you’re feeling stuck in under-fuelling, struggling with energy, or just not seeing the training progress you expect, we’re here to help.

Our Performance Profile gives you insight into where your nutrition is at and what adjustments could help you feel and perform at your best. If you’re ready to break free from restrictive patterns and fuel with confidence, schedule a call with our team or get started by claiming your profile below.

References below:

De Souza MJ, et al, 2021. Randomised controlled trial of the effects of increased energy intake on menstrual recovery in exercising women with menstrual disturbances: the ‘REFUEL’ study. Human Reproduction, Vol.00, No.0, pp. 1–13

Melin, A., et al 2018. Energy Availability in Athletics: Health, Performance, and Physique. Human Kinetics Journals, 29 (2) p. 152-164

Peos, J.et al, 2021. A 1-week diet break improves muscle endurance during an intermittent dieting regime in adult athletes: A pre-specified secondary analysis of the ICECAP trial. PLOS ONE, 16(2), p.e0247292.

Trexler, E., Smith-Ryan, A. and Norton, L., 2014. Metabolic adaptation to weight loss: implications for the athlete. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1).

JAMA, 2006. Effect of 6-Month Calorie Restriction on Biomarkers of Longevity, Metabolic Adaptation, and Oxidative Stress in Overweight Individuals: A Randomized Controlled Trial—Correction. 295(21), p.2482.

Eckert, E. D., Gottesman, I. I., Swigart, S. E., & Casper, R. C. (2018). A 57-Year Follow-Up Investigation and Review of the Minnesota Study on Human Starvation and its Relevance to Eating Disorders, 2(3), 1–19.

Centre for Clinical Interventions. (2018a). Eating Disorders & Neurobiology. Retrieved from https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/Resources/~/media/7644CF6DB09443138A975DEE6EF725DD.ashx